On a visit to the Flemish city of Aalst, Derek Blyth discovers a Carnival parade that likes to shock, a priest that took on the factory bosses and a utopian library.

It looked like one of Bruegel’s mad paintings. The square outside Aalst station was full of revellers drinking beer, hurling confetti and playing brass instruments. They were wearing colourful costumes and singing raucous songs. The shop windows protected by wooden boards as if they were expecting a riot at any moment.

Aalst Carnival has a wild, anarchic character.

Aalst Carnival has a wild, anarchic character.© Cameraad

‘Prepare to be shocked,’ a Flemish friend had warned me, some years ago, when I announced a plan to visit Aalst’s Carnival. (It was cancelled in 2021, and again in 2022, because of the pandemic, but will relaunch on 19 February 2023). She wasn’t kidding. Once a year, Aalst goes insane. No one can explain it fully, but this modest industrial city north of Brussels, population 85,000, has one of the most outrageous Carnivals in the world. It includes a procession of floats with giant figures that mercilessly mock the political events of the past year, along with a parade of men dressed in skirts and fishnet stockings.

Giants Iwein and Lauretta parade through the city centre during Sunday's procession.

Giants Iwein and Lauretta parade through the city centre during Sunday's procession.© Cameraad

I had expected something more orderly, like the Ommegang in Brussels. A colourful parade of people in costumes, something like that. It was after all listed by UNESCO in 2010 as ‘world cultural heritage’ and promoted on a motorway sign as your drive north from Brussels. It looks fun, I thought. But Aalst Carnival has a wild, anarchic character. Maybe not for everyone, but fascinating to observe, all the same.

They have been celebrating Carnival in Catholic Flanders since the Middle Ages. It marks the beginning of Lent, the forty days of fasting that precedes Easter. But Aalst reinvented the festival in the nineteenth century. Its Carnival was organised by shops and cafes to boost the local economy during the dark winter days. But it also served to bring together a community broken by industrialisation.

Aalst reinvented the festival in the nineteenth century. Its Carnival was organised by shops and cafes to boost the local economy during the dark winter days.

Aalst reinvented the festival in the nineteenth century. Its Carnival was organised by shops and cafes to boost the local economy during the dark winter days.© Cameraad

The main parade involves huge lumbering floats that are pulled through the cobbled streets by old trucks and battered farm tractors. Each one is decorated by one of the seventy or so local Carnival societies with giant figures that mock events of the past year. It might be a politician who gets gently ridiculed. Or a celebrity who has been in the news. Or maybe a social issue that needs to be targeted.

Aalst Carnival includes a procession of floats with giant figures that mercilessly mock the political events of the past year.

Aalst Carnival includes a procession of floats with giant figures that mercilessly mock the political events of the past year.© Cameraad

Carnival is seen as an excuse to let off steam, do something outrageous, shake off inhibitions for three days. The social order is upended, so the jester becomes king, the boss can be mocked. On the second day, they toss Ajuintjes (little onions) from the balcony of the town hall. Not real onions, but small sweets. They call it Ajuinenworpen. Onion throwing.

The strangest day is Mardi Gras when thousands of local men parade through the streets dressed as women. And they don’t just wear a dress and some lipstick. The dedicated Voil Jeanetten (Dirty Jennies, they are called in English) put together bizarre costumes involving false breasts and fur coats, along with weird accessories such as old prams, dead herrings in bird cages and vintage lampshades.

'Voil Jeannetten' or 'Dirty Jennies' are men dressed in bizarre costumes involving fake breasts and fur coats, along with weird accessories.

'Voil Jeannetten' or 'Dirty Jennies' are men dressed in bizarre costumes involving fake breasts and fur coats, along with weird accessories.© Cameraad

The Voil Jeanetten emerged in the nineteenth century when the local workers were often too poor to afford a Carnival costume. So, they would improvise by raiding their wives’ wardrobes and adding something absurd like a broken umbrella. Some push prams filled with rattling beer bottles. Or they will carry a chamber pot filled with a mix of speculoos and beer.

The Jeanetten

have often been drinking since early morning. It can get rowdy, my friend had warned me. But there are strict rules. Someone might try to whack you in the face with a wet herring. But that’s the spirit of Carnival everywhere.

The Voil Jeanetten emerged in the nineteenth century when the local workers were often too poor to afford a Carnival costume.

The Voil Jeanetten emerged in the nineteenth century when the local workers were often too poor to afford a Carnival costume.© Cameraad

Mercifully, the Carnival celebrations only last three days. They end with a ceremony known as popverbranding, or burning of the doll, during which an effigy is set on fire. A different figure every year. And then the fire goes out and everyone returns to work the next morning in this quiet industrial city as if Carnival never happened.

The Carnival celebrations end with a ceremony at which a doll is burned.

The Carnival celebrations end with a ceremony at which a doll is burned.© Cameraad

It is meant to be fun, but it isn’t always funny. Sometimes the joke falls flat. People get upset. In 2019, Aalst went too far, many people said. One of the Carnival societies rigged up a float with giant effigies of caricatured Jewish bankers. It was meant to be an insider joke that referred to the Carnival society’s financial problems. But the world didn’t see it that way. The Carnival was condemned as anti-Semitic. There were calls for UNESCO to remove Aalst. And then the mayor surprised everyone by asking for his city to be taken off the list. The event is still listed on the UNESCO website, but with a line drawn through it. Cancelled, you might say.

Stubborn, is the word that comes to mind. Or at least not politically correct. Why would you even want to go there? I thought, as I sat on the train from Brussels.

***

It was a cold day in mid-December when I stepped off the train. The city has an impressive nineteenth-century station designed by Jean-Pierre Cluysenaar to look like a mediaeval castle. It overlooks a square with some old hotels and cafes. I asked a few people for tips on what to do in Aalst. But mostly they were puzzled that I would even think of going there. Ghent is much nicer, I was told.

The nineteenth-century station of Aalst looks like a mediaeval castle.

The nineteenth-century station of Aalst looks like a mediaeval castle.© station hotel

The name Aalst looks like it might be part of a marketing plan to ensure it got to be first in the A to Z of Belgian cities, safely ahead of Antwerp. Famous for something at least. And now of course Aalst Carnival is famous for the wrong reasons. Just try a Google search to see what the internet says.

But I had read an inspiring message in a little booklet published by the tourist office. Aalst vergeet je nooit – ‘You’ll never forget Aalst,’ it promised. The final two letters of AALST at an angle, as if they are falling over, a reference to a popular notion that someone from Aalst nen hoek af is – is slightly bonkers.

The name Aalst looks like it might be part of a marketing plan to ensure it got to be first in the A to Z of Belgian cities

The councillor for tourism, Caroline De Meerleer, had written a short introduction to her city. ‘Dear traveller, you have good taste, that’s for sure,’ she began. ‘By picking up this booklet you prove that you’re interested in something different. And that you find it boring to visit the same old tourist destinations. You are determined to find somewhere that is new and unknown.’

I was starting to like Aalst.

I stopped just for a moment to look at the Hôtel de la Gare. Facing the station, it looks quite shabby. Its rating on hotel booking sites suggests you should stay somewhere else. Maybe the grand nineteenth-century Station Hotel with its antique furniture and chandeliers. Or the intimate and contemporary Georges & Madeleine Apartments, right in the centre.

I headed off in the direction of the centre, looking for evidence of Aalst’s unique mix of elements. It didn’t take long to find something interesting. Back in 2017, the city installed a metal strip down the middle of the shopping street Kattestraat (Cat Street). It is inscribed with local dialect words for children’s games. All involve cats. There’s katjen verlos, katjen achterien and katjen aloe. And for anyone who is puzzled, there are illustrations on electricity boxes explaining how to play the different cat games.

The Grote Markt of Aalst has everything that makes a perfect Flemish square.

The Grote Markt of Aalst has everything that makes a perfect Flemish square.© Cameraad

I was starting to agree with Caroline. Aalst seemed just a little different from other places. And then I reached the Grote Markt. The main square had all the right elements. Town hall, yes. Statue of famous person, yes (make a note to check the name later). Belfry, yes (a UNESCO world heritage building, at least for now). Several cafes with outdoor covered terraces. Everything that makes a perfect Flemish square.

I squeezed inside the café Het Paviljoen opposite the city hall. The owners Didier and Evie describe it on their website as a ‘friendly café with a family atmosphere.’ They have 69 beers on the menu including Safir, the local beer, launched in Aalst in 1939, but now brewed by the giant multinational AB InBev in Leuven.

It was too early for a beer, so I asked for a coffee and checked the tourist office website to find out about the square. The narrow Gothic city hall is the oldest in the Low Countries, it says. It dates from 1225, although the original building burned down in 1380 and the replacement was destroyed during a fair in 1879 when a stray firework set it alight, so a little less old than it claims.

The belfry was built alongside in 1460 and a motto added in 1555 by King Philip II of Spain. Nec Spe Nec Metu – Neither hope nor fear, it reads.

Dirk Martens printed works by Erasmus and Thomas More.

Dirk Martens printed works by Erasmus and Thomas More.© Cameraad

The statue in front of the city hall represents Dirk Martens, a local printer who brought Gutenberg’s invention to the Low Countries and used it to print works by Erasmus and Thomas More.

It began to rain as I left the cafe. Cold, winter rain. Yet even in bad weather, a Flemish square is a human, welcoming urban space. It is, at its best, the place where you go to marry, celebrate, meet a friend, eat frietjes, buy a kilo of onions. Ajuinen, I ought to say.

I wanted to look at the new public library that had opened in 2018. I was struck by the name. Utopia, it was called. A reminder that Dirk Martens brought out the first edition of Thomas More’s Utopia

more than five centuries ago. He was working in Leuven at the time, but Aalst has bagged the book’s title for its library.

I wondered about asking someone, ‘Can you tell me how to find Utopia.’ But I just used the map on my phone, like any sensible person. The library stands on a small square facing a row of worker’s houses painted bright, cheerful colours. It could have been colourful Burano island near Venice, or Nyhavn in Copenhagen. Or maybe even Utopia, the perfect place.

Public library Utopia

Public library Utopia© Cameraad

The word ‘Utopia’ appears in big neon letters above the entrance to the library, along with a map of the fictional island copied from Martens’ first edition. Inside, the building is dotted with other reminders of Thomas More’s famous little book.

The building itself seems to have been shaped by the idea of Utopia. Designed by Dutch firm KAAN, it is a bright, airy building with a vast stepped atrium, elegant wood bookshelves and an attractive cafe. The complex embraces a former nineteenth-century military cadet school now occupied by an academy of performing arts. Its windows look into the library, so you might spot a student playing a violin, or dancers using the rehearsal space.

‘Utopia has become the city’s living room,’ said director Arnoud Van der Straeten.

‘Utopia has become the city’s living room,’ said director Arnoud Van der Straeten.© Cameraad

The library has an inspiring programme. You can organise a meeting, play a board game or listen to a music critic run through their favourite vinyl records. ‘It has become the city’s living room,’ said Utopia director Arnoud Van der Straeten in an interview with a Dutch newspaper.

However, I had not come in search of Utopia, but to find the soul of Aalst. It seemed the best place to visit was the ‘t Gasthuys – Stedelijk Museum, or city museum. It was a short walk to the former hospice ’t Gasthuys on the old fish market square. Dedicated to the story of the city and its inhabitants, the mediaeval building has been sensitively restored with whitewashed walls, tiled floors and a walled herb garden. It feels like a calm, contemplative place.

‘t Gasthuys – Stedelijk Museum is dedicated to the story of the city and its inhabitants.

‘t Gasthuys – Stedelijk Museum is dedicated to the story of the city and its inhabitants.© Cameraad

But then all hell breaks loose on the first floor where two large rooms are dedicated to Carnival. You are surrounded by masks, costumes and mad scenes. One section is dedicated to the Voil Jeanetten and their ridiculous prams, fake breasts and bird cages. Another room is filled with photographs that evoke the three days of surreal chaos.

But then the mood changes. A quiet upstairs room is dedicated to the twentieth-century Aalst painter Valerius De Saedeleer. I was captivated by his subtle, mystical paintings of the Flemish landscape that could almost have been done by Bruegel. It only needed a crow perched on a tree stump. Looking through a window, I noticed a statue of the artist in the square outside. A large, contented man.

Aalst-born artist Valerius de Saedeleer (1867-1941) is known for his mystical paintings of the Flemish landscape.

Aalst-born artist Valerius de Saedeleer (1867-1941) is known for his mystical paintings of the Flemish landscape.© Wikipedia

The museum has also dedicated an entire room to the local Jesuit priest Adolf Daens, who enraged local employers and the Catholic Church in the late nineteenth century by campaigning for a minimum wage, universal suffrage and an end to child labour. His life inspired a novel by the Aalst writer Louis Paul Boon, along with a film and a musical. And the museum offers its own version of the Daens story through newspaper articles, photos and pamphlets.

***

It was time for lunch. It isn’t hard to find food in Aalst. Or beer for that matter. The tourist office claims the city has 345 restaurants and bars. I ended up in a tiny snack bar called De Soeptrein in a narrow cobbled lane. It was a friendly, local place with three iron pots of homemade soup bubbling away on the counter. I had tomato soup served with a thick hunk of bread. Comfort food for a winter day.

Inside the Church of Saint Martin

Inside the Church of Saint Martin© Cameraad

And then I headed to the Sint-Martinuskerk, the beautiful gothic church dedicated to Saint Martin. The building is currently being restored. The work began in 2003. But it won’t be finished until 2027. In the meantime, you can climb a temporary wooden staircase and peer through a small window to see the work in progress. On a weekday, you might be able to watch a restorer touch up a painting or repair a broken altarpiece. And if you want to see more, there is a virtual tour on the Visit Aalst website.

Restorer at work in the Church of Saint Martin

Restorer at work in the Church of Saint Martin© Cameraad

The church is the proud owner of a painting by Rubens. It is an odd work titled De Pestlijders, or The Plague Victims, that was commissioned by the rich and powerful hop merchants of Aalst. As he worked on the painting, Rubens must have been reminded of his first wife, who died of the plague.

***

I knew by now that Aalst was once an important industrial city. It boomed in the nineteenth century when its factories produced textiles, nylon stockings, and beer. Even today, Aalst is dominated by industry, with the massive, menacing Tereos factory producing sugar and starch on the edge of the old quarter. It looms above the modest workers’ houses on a former island called Chipka, belching hot steam into the sky, spreading smells across half the city.

But many of the old factories have closed down. Some have been demolished, others have become apartment complexes or creative hubs. One of the most interesting is the abandoned Cimorné factory, named after a curious cement called ciment orné that was decorated with broken glass. The 1920s industrial interior has been taken over by several small businesses including a bike store, hipster barber, sourdough bakery and a plant shop with greenery hanging from an old canoe. You can drop in here for a healthy lunch and maybe hit a day with a plant workshop or a concert on the agenda.

The abandoned Cimorné factory has been taken over by several small businesses.

The abandoned Cimorné factory has been taken over by several small businesses.© Cameraad

Sarah runs the plant shop Drift. Her ideas, expressed a few years ago in a letter to potential customers, seem almost utopian. ‘We love the sound of a twig snapping in the silence of a forest, the glow of gold and bronze, the fragility of moss and the roughness of stone.’ On her website, she is a little less poetic. ‘Get dirty,’ she says.

The factory interior is lit by circular lamps made from suspended bicycle wheels. There is an indoor wooden bike track. The bike theme even extends to the toilets where the walls are covered with nostalgic photographs of Belgian cycling heroes.

‘If you want good coffee, you should go to Philimonius, I was told. The coffee shop is located in a narrow lane with small and independent shops. The interior has a hipster look with vintage furniture, a window counter where you can perch and a small shop selling books and stationery. Locals swear the coffee served here is the best in town.

De Werf, one of the cultural venues in Aalst.

De Werf, one of the cultural venues in Aalst.© Cameraad

I was beginning to understand that Aalst was going through a period of change, from a rather grim industrial city to a cool, cultural place. It has built a stunning cultural centre called De Werf, and created a new urban park on the site of a former factory, its tall brick chimney converted into a climbing wall.

The city has also introduced a new traffic plan that favours bicycles and pedestrians (although there is a huge parking garage next to the station for anyone who arrives by car). And of course, it has built Utopia.

The city proudly displays its new identity in a new seven-minute film projected in a 360-degree cinema. It shows off the tourist sights, the nature reserves and the Cimorné factory. And ends with the Carnival that turns everything on its head.

***

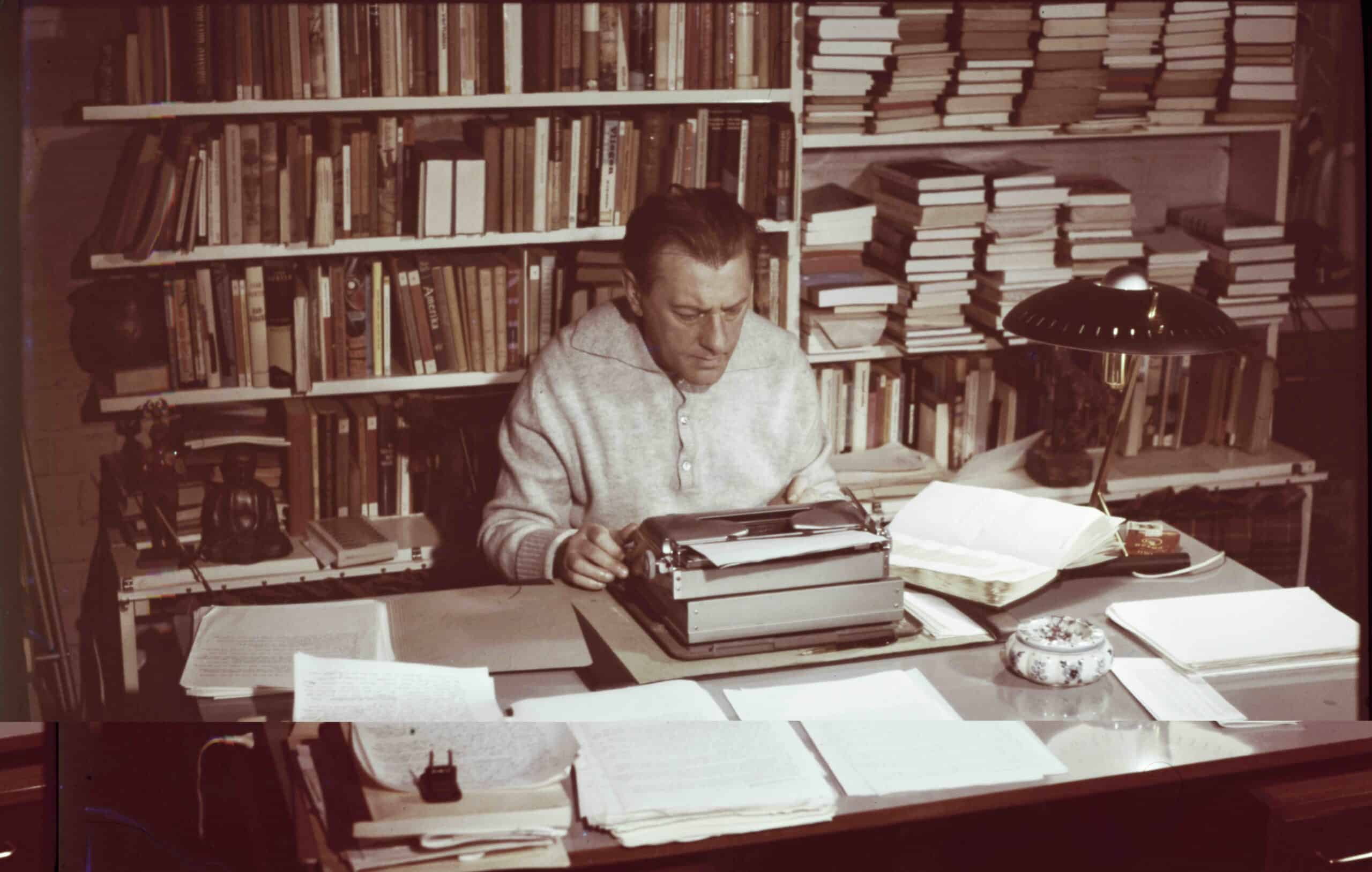

I had an hour to fill before the train to Brussels. Just enough time to find out about the local writer Louis Paul Boon. Earlier, I had spotted a statue of Boon outside the library. It shows the writer sitting on a chair, bending forward as if he is engaged in conversation. The chair opposite is empty, waiting for someone to sit down.

Louis Paul Boon (1912-1979) is one of Flanders' best-loved and most notorious writers.

Louis Paul Boon (1912-1979) is one of Flanders' best-loved and most notorious writers.© Jo Boon/heirs Boon

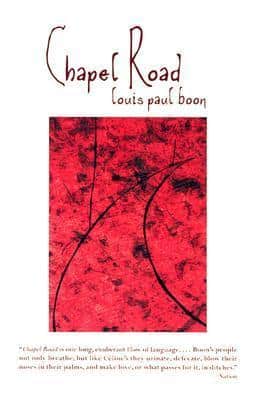

Inside the library, Boon’s life is illustrated in a timeline. It shows the depressing little house where he was born in 1912, the author in military uniform, and the covers of his many novels. His most famous work is

Kapellekensbaan, translated into English as Chapel Road.

First published in 1953, this experimental novel tells the story of a local girl called Ondine who lives in a slum dwelling on Aalst’s Kapellekensbaan. Her aim is to become rich in a society that has given up any idea of morality or social justice. ‘The most powerful epic to come out of Flanders this century,’ wrote Elsevier

magazine.

As well as his subversive fiction, Boon was known for his enormous collection of erotic photographs. He preserved them in an archive he called De Fenomenale Feminateek

(The Phenomenal Female Library). It contained 22,600 images carefully organised in fourteen volumes.

Boon caused trouble in 1972 with the publication of his pornographic parody Mieke Maaike’s obscene jeugd – Mieke Maaike’s obscene youth.

Boon caused trouble in 1972 with the publication of his pornographic parody Mieke Maaike’s obscene jeugd – Mieke Maaike’s obscene youth.The literary world has struggled to come to terms with Boon’s obsession. The Amsterdam publisher Meulenhoff/Manteau issued a small selection of Boon’s images in 2004. But an exhibition planned for Antwerp in 2008 was banned by the provincial government on the grounds of ‘limited artistic value’. Ten days later, a selection of photos went on show at a Ghent literary festival. The following year, Antwerp changed its mind about its artistic value and organised its own exhibition.

Boon caused more trouble in 1972 with the publication of his pornographic parody Mieke Maaike’s obscene jeugd – Mieke Maaike’s obscene youth. The story of a sex-crazed teenage girl, it went through twenty-three editions, making it a classic of Flemish erotic literature. But it has not helped Boon’s already tarnished reputation.

And yet Boon may have come close to winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1979. He had been invited to the Swedish embassy in Brussels. Possibly to be told that he had won. He would have been the first (and, to this day, only) Dutch language author to win the prestigious award. But, tragically, Boon died at his writing desk on 10 May 1979, and the award went to the Greek poet Odysseus Elytis.

On the train back to Brussels, I realised Louis Paul Boon sums up the spirit of Aalst. He was a rebel, an anarchist, a fighter. And a pornographer, you might have to add. A complex person. But then Aalst is a complex city.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.